The past week has seen a surge in violence across western Hama and Homs following nearly two months of relative calm. Each attack was different in context, but all point to the same underlying problems: a lack of checkpoints in Syria’s countryside and a lack of inter-communal dispute resolution mechanisms.

Spiraling Revenge

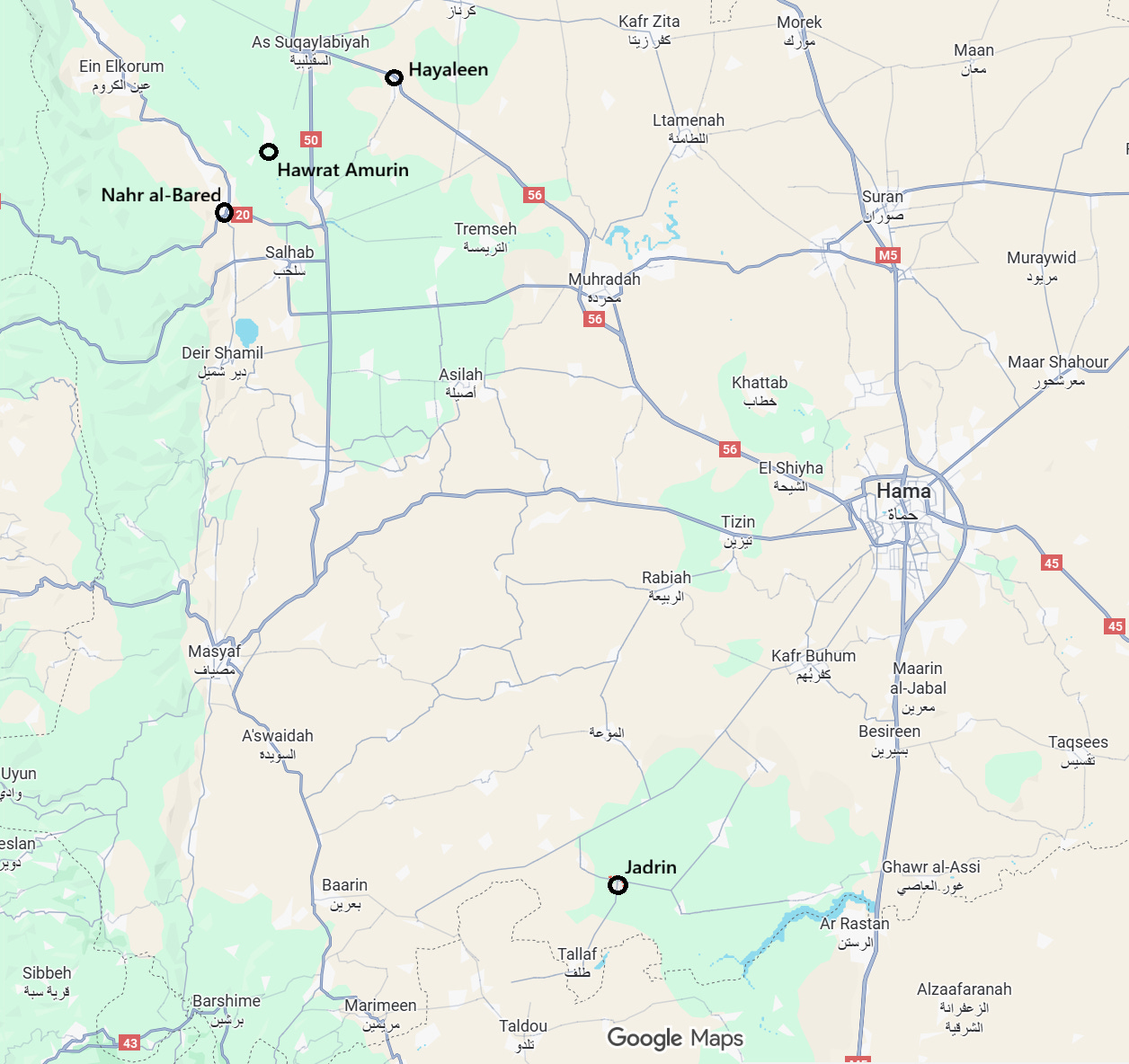

The first major incident began on September 10, when an Alawi girl from the western Hama village of Hawrat Amurin was stalked and raped by two men along the road outside her town. The perpetrators were driving a “Halfawiya” style truck - a small cargo vehicle typically used to transport livestock or agriculture product. However, the lack of government communication around the investigation and general distrust towards the government fueled social media rumors that the criminals were actually members of the security forces.

Two weeks later, on September 23, an unknown group from the nearby Alawi village of Nahr al-Bared kidnapped a soldier from his checkpoint outside the town. The kidnappers published a video online torturing the soldier, saying it was in revenge for the rape of the woman.

The next day, the family of the kidnapped man went to Nahr al-Bared and met with the Mukhtar and village elderly, demanding to know the identities of the kidnappers and for his return. At the same time, a group of Sunnis from nearby villages stormed Hawrat Amurin with guns, looting and attacking homes and killing one elderly man when he refused to give up his motorcycle. Nearby General Security and Ministry of Defense units quickly responded and set up checkpoints around the town.

At this point, the rape case from two weeks prior had spiraled into widespread inter-communal violence. In order to end the escalation, a group of religious and community leaders began holding dialogue sessions. Priests and General Security officials from the large nearby city of Suqaylabiyah took the lead. One participant described the subsequent series of meetings:

“We met with residents of Hawarat Amurin and we agreed with them on the fact that the government’s duty is to protect all its citizens and we said our condolences to the killed one’s family, may God bless his soul and may he rests in piece.

It was agreed upon to form a small council to be always directly in touch with the Ministry of Interior about any problem in the area and to prove that they are not involved themselves.

Then, another meeting happened in Nahr al-Bared, the village where the kidnapping happened, as they were afraid and nervous thinking they might be attacked as well. They were assured and we told them even if the kidnapping happened in the village, or on it’s roads or on a nearby area, it doesn’t mean that you are accused. But if you see or hear anything that is related to the incident you must report it. Because some people were making them horrified and weren’t letting them get in touch with MoI, [here implying that regime insurgents were threatening the townspeople] I got them in touch with the MoI and they took phone numbers and it was agreed that four or five people of the village would stay in touch with the MoI about any big problem.

We also told them about the sitting we had in Hawrat Amurin and how positive the results were, and they asked to join our group for all of us to be in one group to work to protect the area.”

In essence, the social and religious leaders of this area are now forming a Civil Peace Committee in close coordination with local security officials. Had such a system been in place two weeks prior, it’s likely that none of this violence would have happened. These types of communal intermediary networks are rare, but where they exist they have very positive impacts at the local level.

Lack of Security

Yet such systems cannot prevent the other types of revenge and sectarian crimes that have also plagued the region this past week. On September 27, residents of Jadrin, an Alawi village in the southern Masyaf countryside, took to the street in protest of the removal of a military checkpoint from the entrance to their town. The next day, four men were murdered nearby while returning from a construction site. On September 30, MoI officials announced the arrest of the murderers, but the crime itself never would have happened if the checkpoint had not been removed, and the fear and distrust the murders have caused cannot easily be resolved.

The next day, back near Suqaylabiyah, three brothers were kidnapped from their home and executed outside the village of Hayalin. Unlike the other crimes, this one had no sectarian dimension as it is a Sunni village. Rather, it was purely a case of old revenge. However, the ease with which the perpetrators kidnapped and murdered the men again speaks to a shocking lack of security in this part of Hama.

Lastly, late at night on October 1, gunmen drove a motorcycle from the Homs-Tartous highway up the main road into the Christian-dominated Wadi Nasara region and killed two Christian men in the village of Anaz. Wadi Nasara had, since December 8, been free of any of the instability and violence experienced in other parts of the coast, and this blatantly sectarian attack came as a shock to the community. It is unclear how the perpetrators entered the town given the presence of a security checkpoint on its outskirts.

Engage Communities, Expand Checkpoints

Despite the different motivations and contexts of this week’s crimes, all share one underlying factor: a lack of security checkpoints is enabling sectarian and inter-communal violence. These parts of western Hama and western Homs are particularly vulnerable given the dense mixing of Sunni, Alawi, and Christian villages and the bloody history of regime militia recruitment and massacres that occurred in these towns during the civil war. Of any part of Syria, it is here that the physical security apparatus should be extensive and prioritized.

The response to these killings by locals has been unanimous: expand the checkpoints. Prominent pro-Damascus media figures have echoed the same online. At the same time, local officials should be pushed to support the creation of Civil Peace Committees or Reconciliation Committees in these areas, forming locally-run institutions that can support the work of security officials while also mediating between communities and sects when tensions rise. These systems exist in various forms across the country, but they have not been institutionalized. It is time for senior officials in Damascus to prioritize the conditions in Syria’s countryside, before more preventable violence metastasizes.