Examining Coastal Massacre Investigations

How do the Independent Committee's findings compare with Reuters and others?

The past two weeks’ violence in Suwayda has renewed international attention on Syria’s new government and its treatment of minorities. Many comparisons have been made to the March massacre of Alawite civilians in Syria’s coast, an event for which many questions remain. The independent National Committee for Investigation and Fact-Finding submitted its final investigation to President Sharaa on July 20 and on July 22 held a press conference providing an overview of their findings. Yet the fact that the report in its entirety remains private has limited the public impact of this investigation. In its stead, a series of public reports by both human rights organizations and news outlets have become the core of the public narrative of what happened and who was responsible for the violence from March 6 to March 9.

Among these is a June 30 investigation by Reuters which claims to address two aspects of the massacres: the killings of Alawite civilians and the pro-government armed groups responsible. The report does a good job of documenting the first issue, and falls far short in its claims on the second. The third major investigation recently published comes from the highly regarded Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression (SCM), which looked both at the killings of civilians but also the coordinated insurgency that triggered the wider Sunni mobilization.

The Victims

There are now three credible sources for the scale of violence during those three days in March, all of which roughly agree with each other.

SCM found 1,060 Alawite civilians were subjected to extrajudicial executions by pro-government armed forces across 61 distinct locations in Latakia, Tartous, and Hama. Among the murdered were 71 women and 61 children. The report notes that this number does not distinguish between civilians and those Alawite men who had taken up arms against the state, but that the execution of surrendered and unarmed combatants (which certainly occurred extensively) is itself a crime. The report also documented by name the deaths of 218 security personnel.

The Reuters investigation, released a few weeks after SCM’s, reports 1,479 Alawites killed by pro-government forces, relying largely on community-documented ‘martyrdom’ lists and visual evidence of the dead. The report also maps out 40 communities across Latakia, Tartous, and Hama where massacres occurred. The investigation did not attempt to document the deaths of security personnel, but referred to Sharaa’s statement that “more than 200” had been killed.

The Investigative Committee reported 1,426 mostly Alawite civilian deaths (there were at least dozens of Sunni civilians killed in the initial Alawite insurgent attack, as documented by both SCM and the Committee), among them 90 women. It also documented 238 security personnel killed in the March 6 uprising. All deaths were documented by name, as the Committee spent four months traveling between coastal communities meeting with survivors and community leaders.

A Pro-Assad Uprising

The SCM report provides an exhaustive timeline of the start of the March 6 events, beginning with a region-wide, coordinated uprising by pro-Assad and anti-Damascus Alawites that successfully overran every government position in rural Latakia and Tartous. Through the course of the evening, these insurgents captured the Naval Academy in Latakia and nearly every district capital in both governorates.

In Latakia governorate the violence was particularly pronounced, with many General Security members killed or executed after surrendering (as noted in the Investigative Committee’s conference and seen in videos at the time). In Tartous, however, most GSS units were able to negotiate their safe exit to Tartous city - although this was not the case in and around Baniyas, according to locals.

This uprising was not spontaneous, having been planned for at least weeks in advance. During my weeks in the coast from late January until mid-February I heard extensive testimony from Alawites about growing anger towards Damascus and Sunnis more broadly over a variety of economic and social issues, all underpinned by the ongoing violence against Alawites in Homs committed by government security forces. These combined factors created a fertile atmosphere for pro-Assad insurgent networks to radicalize people and impose a belief that violence was the only way forward.

In mid-February I met with a militant Alawite sheikh who explicitly threatened the government with “thousands of Alawite youth who will take up their arms the moment we call on them to do so” while at the same time stating that the “Alawite leaders” - as he described them - were running out of patience with Damascus. I know that other researchers heard similar statements from some Alawite leaders during this time, some indicating plans for a broader mobilization in early March.

SCM describes how the attacks began: “On 6 March 2025, unknown assailants opened fire on General Security personnel to prevent them from arresting wanted individuals from the village of Beit Ana in rural Latakia. This was followed by a series of organized attacks and ambushes against General Security, where armed groups, believed to be linked to the former regime – whose numbers we could not determine – attacked military and civilian sites and roads in the governorates of Latakia, Tartous, Homs, and Hama in a coordinated and simultaneous manner.”

At that time I was speaking with a friend who has family in Beit Ana. His family told him in that moment how trucks full of guns were brought into the town by ex-regime soldiers who then called on the youth to join the fight against Damascus. Other Alawite activists in Tartous later told me that many men had joined the insurgents those first hours as a result of intense propaganda campaigns claiming Damascus planned to kill all Alawites and that several foreign countries were coordinating a military intervention alongside the insurgent leaders. When this foreign intervention never came, but rather tens of thousands of armed Sunnis, most of these last minute supporters threw down their weapons and fled.

The Reuters report heavily downplays this initial uprising, the trigger for the wider Sunni and government mobilization, providing just a single anecdote about a “mercenary” turned GSS member killed in Baniyas. Beyond just the scale of the uprising, the loss of most government-run checkpoints throughout the coast ensured free movement for any armed group throughout the Alawite villages in the ensuing days. The brutal fighting that night also served as a key mobilizing factor for both Sunni civilians and government-aligned armed groups, as GSS members besieged by insurgents or under threat called on their friends and family to come to the rescue.

For example, HTS’s 400th Division (incorrectly referred to as Unit 400 in the Reuters report) lost more than 25 soldiers during the initial uprising in the Jableh countryside, likely contributing to the degree of violence the survivors would later inflict on Alawite civilians in the villages near the attacked positions.

The Perpetrators

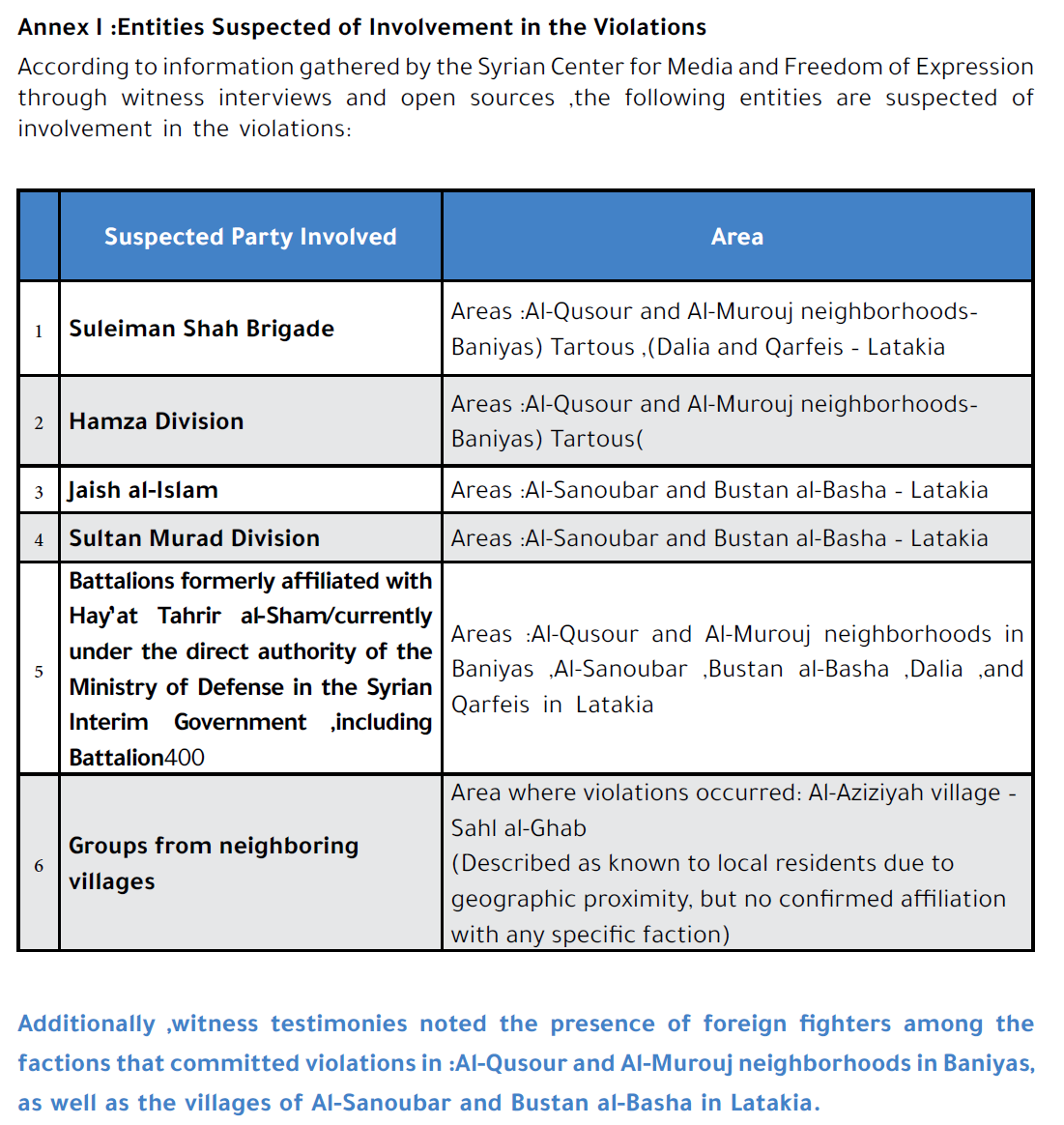

According to SCM, “Armed formations affiliated with or loyal to the Transitional Government's Ministry of Defense, alongside foreign fighters, were involved in carrying out the violations,” which ranged from looting and harassment to extraductal killings. The investigation also highlighted the “calls for general mobilization and statements from tribes, religious leaders, and civilian figures in various parts of Syria,” which contributed to the flow of armed Sunni civilians into the coast and fueled the calls for sectarian-motivate revenge violence.

According to the Investigative Committee’s press conference, “the commission identified individuals and groups linked to certain military groups and factions from among the participating forces [pro-government and government-controlled]. The commission believes that these individuals and groups violated military orders and are suspected of committing violations against civilians.”

The Reuters report goes far further, naming explicitly a distinct set of government-controlled military units which the author claims committed each massacre in each town. The report attempts to link the overall number of killed civilians with specific units that were known or claimed to have been in those areas. For example, it claims that:

HTS and Ministry of Interior forces were “involvement in at least 10 sites, where nearly 900 people were killed”

The Syrian National Army factions Suleiman Shah and Hamza Division were present “in at least eight different sites where nearly 700 people were killed”

Jaish al-Islam, Jaish al-Ahrar, and Jaish al-Izza, “were present in at least four sites where nearly 350 people were killed”

“The Turkistan Islamic Party, or TIP, Uzbeks, Chechens, and some Arab fighters in six sites where Reuters found nearly 500 people were killed”

Armed Sunni civilians were present in “the village of Arza and in the city of Baniyas, where a total of 300 people were killed.”

There are several core issues with this framing, which appears intended to both directly blame only the named factions as well as put most of the blame directly on HTS. First, Reuters counts the same massacres multiple times (the listed numbers add up to nearly 3,000 dead). This leads into the second, most basic problem with attribution: many different armed groups moved through every location during the course of the three-day violence.

Attributing perpetrators based purely on presence is a reckless method of investigation for the March 6 massacres because of the sheer number of forces involved in and moving around the area. Many different factions moved through the same towns within hours of each other, and many witnesses have differentiated the actions of these armed groups.

A recent Syrian Archive report explores the presence of armed groups - constituting the entire range of opposition factions and mobilized civilians - across the coast during this time. We identified 24 distinct armed opposition groups who were already deployed to or arrived to the coast after March 6, among these were elements from 12 factions of the Syrian National Army, 4 from the HTS-allied National Liberation Front, 4 legacy HTS divisions, and 4 newly formed Ministry of Defense divisions.

SCM’s report more accurately reflects this complexity than Reuters, naming more than half a dozen factions along with civilians who were present in the same areas of Baniyas and southern Jableh:

But while all of these factions, as well as tribes and civilians, were present, not all are clearly linked to executions or even to any violations at all. Furthermore, there are cases where the same faction is accused of committing violations in one area, and not in another.

Jableh

Recent debate over the role of Abu Amsha’s Sultan Suleiman Shah Division in the coastal massacres underscore this later point. One potential reason for the conflicting claims of his unit’s actions could be that the faction changed its behavior half-way through the events.

According to one Alawite activist who works extensively documenting violations in the Jableh region, Amshat fighters were directly involved in massacres in Jableh city when they first arrived to the area (the SCM report covers in detail the arrival of pro-government forces to Jableh). But by the end of March 7 the unit was facing heavy online criticism and accusations of widespread violations. Therefore, as the faction withdrew its fighters from Jabelh through the Ain Sharqiyah region on March 8, the unit’s officers ensured everyone acted professionally and respectfully. The aforementioned activist met with the Amshat brigade commander when he arrived in the man’s village, confirming that the group committed no violations in the area.

Bahlouliyah

Bahlouliyah is another case involving multiple factions present in the same town, with victims clearly differentiating the actions of each faction. In the Bahlouliyah region, Faylaq al-Sham was one of the first armed groups to arrive. According to one local I spoke with, the Faylaq commanders were respectful and professional as they searched the town. When they left, the commander gave everyone his phone number and said to call him if there were any issues. Later that day, another faction arrived - the witness does not know their name - and began looting homes and killing civilians. The man called the Faylaq commander, who returned and expelled the faction from the town. Faylaq al-Sham has remained in the Bahlouliyah and Haffeh regions since March where it has a widely positive reputation.

Baniyas

Baniyas suffered greatly under a deluge of pro-government factions and armed Sunni civilians. Here witness testimony both demonstrates the complexity of direct attribution and also the distinction between types of violations different factions committed.

Two months ago I published a detailed report on my interview with two survivors of the Baniyas massacre. It is worth reading in full to fully understand this dynamic, but in short: there were five distinct armed groups who entered the Qusour Neighborhood across a 24 hour period, including foreign fighters. Some of these groups are only known to have looted and abused civilians, others are accused of carrying out most executions. Local civilians, bedouins, and Roma also stormed the neighborhood, though again survivors make a clear distinction between those that only looted (Roma) and those who engaged in extrajudicial killings (locals from the countryside).

Qadmus

After the violence in Baniyas ended, multiple armed groups moved up the Masyaf highway to liberate the Ismaili city of Qadmus, which had been besieged by hundreds of local Alawites since March 6. These convoys included General Security members, HTS units, and one faction known to have been involved in killings in Baniyas. According to Ismaili officials who coordinated closely with government officials organizing this convoy, the criminal faction had left first, spurring the quick deployment of the GSS and HTS units to try and ensure the faction did not commit new massacres. In one village, Hataniyah, this faction gathered 12 men in the local Alawite shrine and executed them. It then arrived on the outskirts of Qadmus and began burning some Ismaili homes before the government forces arrived and stopped the attacks. General Security units spent the next two months trying to prevent and resolve continued violations by this military faction until it was eventually withdrawn.

Sanobar

Sanobar perhaps best exemplifies the difficulty of attribution based on unit presence. As documented in the Syrian Archive report, massive convoys consisting of multiple factions were frequently stopped on the coastal highway outside Sanobar between March 7 and March 8. At least three SNA factions are clearly identified as being here during this time: Hamza Division, Ahrar Sharqiyah, and the Sultan Murad Division. HTS’s 400th Division was already deployed in this area before March 6 as well. Which of these units was responsible for which violation is difficult to know.

Clarity Needed

The Reuters report goes one step further, directly accusing senior Ministry of Defense officials of ordering these massacres, something explicitly denied by the Investigative Committee. Reuters cites alleged Telegram messages between military commanders in the coast and the MoD spokesman, Hassan Abdel-Ghani, including one in which he responds to information about crimes being committed against Alawite civilians with “May God reward you” and others which allegedly show him directly coordinating the movement of units in the coast.

These messages are the only evidence that senior MoD officials condoned and/or directed the attacks against Alawite civilians. Reuters provides no evidence of their veracity, but rather heavily indicates that these alleged messages were shown to the author by Abu Amsha, who himself has embarked on an extensive public relations campaign after March 6, and who in private is not shy about his hatred of Syria’s new leadership. It is not clear if Reuters understands the political dynamics between Abu Amsha and Damascus, or if it did its due diligence to verify whether an MoD spokesman was truly directing military operations via Telegram.

Yet regardless of what extent senior leaders had control over the situation in the coast on March 6, they are ultimately required to hold those perpetrators accountable. The government has also failed to rebuild the trust of most Alawites in the wake of the massacre, with senior officials remaining largely silent about the devasting events and their impacts on civilians.

The independent Investigative Committee claims to have submitted to the authorities the names of nearly 265 Alawite men responsible for attacks against security forces, and another nearly 300 members of government-aligned forces responsible for violations against Alawites. Yet without a public record of the investigation, the Committee’s findings will do little to remove the obscurity of the events of that week. Without this, politically-motivated narratives on both sides will continue to hold sway, crowding out more objective work like that of SCM and the Syrian Network for Human Rights, and fueling distrust in the new security forces and central government.

The lack of transparent accountability for the March 6 massacres has only exacerbated reactions to the newest round of violence in Suwayda. Anti-Damascus activists now point to the extrajudicial killings of Druze civilians - committed both by security forces and by local armed Sunnis - as proof that Damascus is embarking on a systematic campaign against minorities. To prove otherwise, Syria’s new leadership must once again hold the perpetrators of these newest crimes accountable - in transparent and public process - and enact genuine reforms within the Ministry of Defense, which is clearly bereft of discipline and professionalism in many units.

The necessary next steps for Damascus are simple: arrest the perpetrators named in the Committee’s coastal report, make the report public, ]be fully transparent in all accountability measures against security forces responsible for violations during and after March 6, and stop deploying MoD units to deal with internal security issues until the new army is truly professional.

Excellent work Greg. Thank you.