An Officer's Journey Through Jabal Zawiyah's Revolution

How Feras Bayoush went from Air Force Officer to Free Syrian Army commander

In August I published the story of Kafr Nabl’s revolution, how the town known for its peaceful protests was invaded by Syrian regime forces in June 2011 and gradually developed its own local armed opposition faction until accidently liberating itself in August 2012. Kafr Nabl was just one part of the broader revolutionary movement in Idlib’s Jabal Zawiyah. Here I take a deeper look at the military history of Jabal Zawiya in 2011 and 2012, bookended by the experiences of one of Kafr Nabl's revolutionary heroes, Fares Bayoush.

It was April 1, 2011 when Lieutenant Colonel Feras Bayoush returned to his hometown of Kafr Nabl in southern Idlib. It was his first visit since the Arab Spring had begun in Tunisia three and half months earlier. “When the uprisings broke out in Tunisia, followed by Egypt and Libya, we were sitting in my office and began to talk cautiously about these revolutions,” he recalls, “we still didn't know the officers' political affiliations, regardless of their sectarian affiliation. I looked at their faces to determine who supported these revolutions and the right of peoples to self-determination.”

When demonstrations began in Syria in early March, Feras met with two other officers he knew he could trust, Major Saleh and First Lieutenant Talal. “The three of us spoke frankly about what we could do as soldiers if the demonstrations spread.” Major Saleh joined Feras on the short visit to Kafr Nabl, intending to just pay their respects for a friend’s recently deceased father before returning to the office in the Deir Ez Zor Military Airport. The visit would set all three men upon an irreversible path.

“Upon arriving at the entrance to Kafr Nabl, we were surprised to find a demonstration of 150-200 demonstrators chanting "God - Syria - Freedom - That's it!" We looked at each other with a look that held many words. I told him [Saleh] that since Kafr Nabl had participated in the demonstrations, he could be confident that the demonstrations would spread throughout Syria.” Rural southern Idlib, a hilly farming region known as Jabal Zawiyah, had just erupted in protest. This day would mark the start of unending months of protests from the smallest village to Idlib’s largest cities.

Feras and Saleh returned to Deir Ez Zor that evening and immediately went to work. “We met at my house and decided to carry out a military operation at Deir ez-Zor Airport,” says Feras, “We would coordinate with the other formations in the area. Each officer was tasked with communicating with his fellow officers from the brigades stationed in Deir ez-Zor.” Across Syria, many of the military officers who would go on to defect and lead Free Syrian Army units were embarking on a similar process, attempting to coordinate internal coups within their formations to bring down the regime without a large war.

“The idea was to make Deir ez-Zor a city safe from the regime, similar to Benghazi at the time, as it was remote from the center and had excellent facilities.” Yet, as with all other attempts, the regime’s intelligence directorates, the mukhabarat, had uncovered the conspiracy. Lieutenant Talal was arrested while in Dara’a, forcing Feras, Saleh, and the others to abandon their plans and lay low. Yet by June nothing had happened to them, Talal had not betrayed their plans to his torturers, and so the officers renewed their work.

By the end of the month Feras knew he had to evacuate his family from the military housing in Deir Ez Zor or risk the regime using them as hostages should he be uncovered. On June 30 Feras arrived back in Kafr Nabl, his family in tow, in what would be his last visit for more than a year.

This situation in the town had changes significantly since April. On June 5, locals in the nearby city of Jisr Shoughur stormed the city’s two Military Intelligence headquarters, killing all 120 regime personnel. The unit had increasingly been killing and detaining protestors in the city in recent weeks. The regime responded harshly, sending huge numbers of military units to the governorate.

“On the second day of my vacation, regime forces began entering Kafr Nabl, shooting their guns in the air. They began deploying at the entrances to Kafr Nabl, set up checkpoints, and declared a curfew in the city from 8:00 PM to 7:00 AM. Every day at sunset, they began shooting in the air. So, I went to the command center, where a brigadier general, a colonel, and a lieutenant colonel were present. I asked them about the reason for the curfew and the reason for the gunfire. The brigadier general responded that day and lifted the curfew. That day they respected that I was an officer like them and that what I was saying was true.”

Withe the army’s deployment, many of the revolutionaries in Kafr Nabl began to seriously debate the need for armed action. Feras met with them over the ensuing days, though, and warned them against military action. “The forces were unbalanced and the regime's response would be extremely violent,” he remembers telling them, “I advised them to continue peaceful demonstrations and that the right time for military action would come when there were significant defections within the army.”

The men took his advice, and the city settled into a period of frequent protests. However, as the regime’s forces increased their violence against civilians and detentions and killings of protest leaders, Kafr Nabl’s revolutionaries began to skirmish with the local regime garrison, particularly in early 2012 as defectors returned to the town and brought with them their expertise.

Feras witnessed none of this. On July 20 his leave ended and he returned to Deir Ez Zor. Four days later, he was arrested by the Air Force Intelligence.

Prison, and Jabal Zawiyah’s Revolution

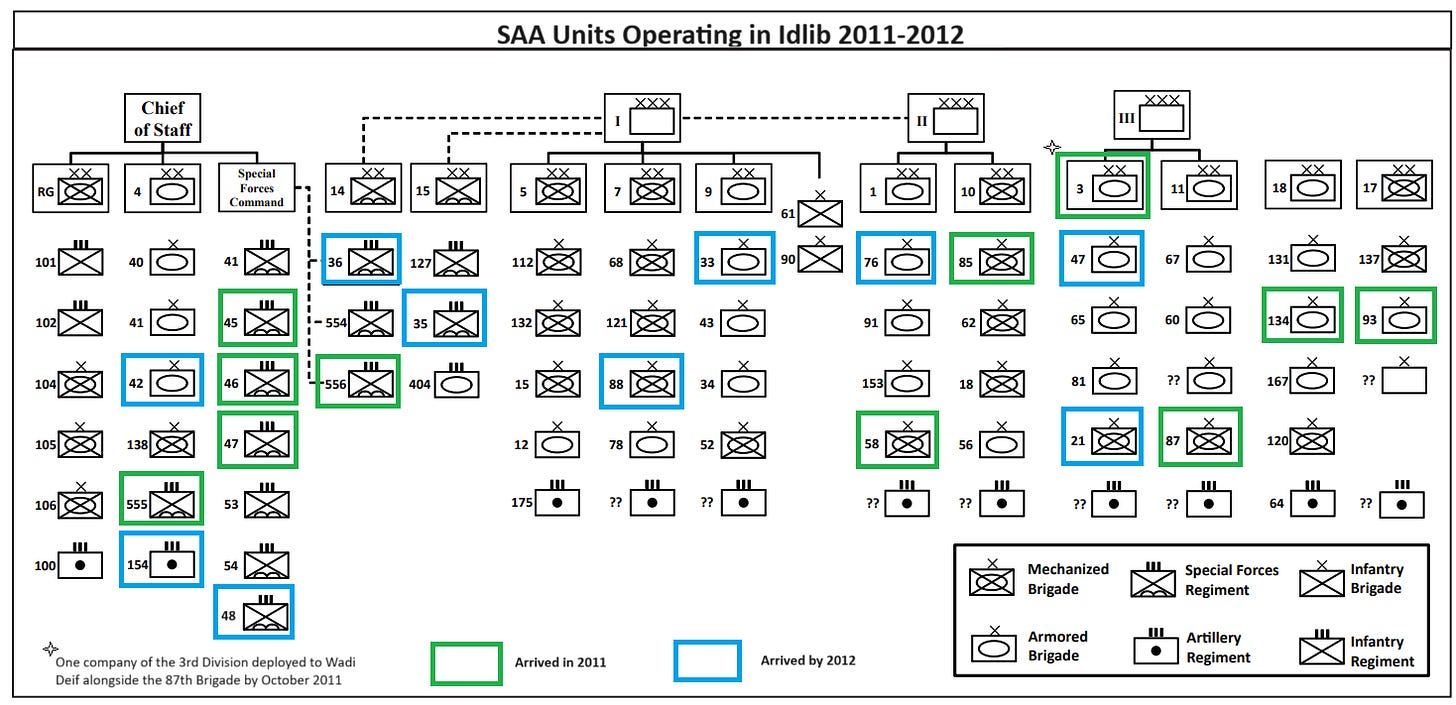

What Feras saw in Kafr Nabl on July 1, 2011 was just one small part of a much larger operation being conducted by the Assad regime. The regime’s 46th Special Forces Regiment had already been fully deployed in the governorate, using a newly established base in Mastoumeh. Now, throughout June and early July, elements of two additional Special Forces regiments and two army brigades joined them. Units of the 45th Regiment left Dara’a, where it had deployed to suppress protests on March 30, 2011, and arrived in Jisr Shoughur, supported by the 10th Division’s 85th Brigade. To the east the 14th Special Forces Division’s 556th Regiment moved from the Homs countryside to the area between Maarat al-Numan and Khan Sheikhoun. The 17th Division’s 93rd Brigade deployed to Jisr Shoughur and Jabal Zawiyah at the same time

The regime’s military deployments and operations immediately following the June Jisr Shoughur battle put significant pressure on the nascent armed opposition in Idlib. Two new organizations had just announced their formation: The Free Officers Movement on June 9, and the Free Syrian Army on July 29. These groups, based out of Jabal Zawiyah and southern Turkey, respectively, became hubs for regime defectors and helped to foster coordination between local armed factions across Idlib and rural Aleppo.

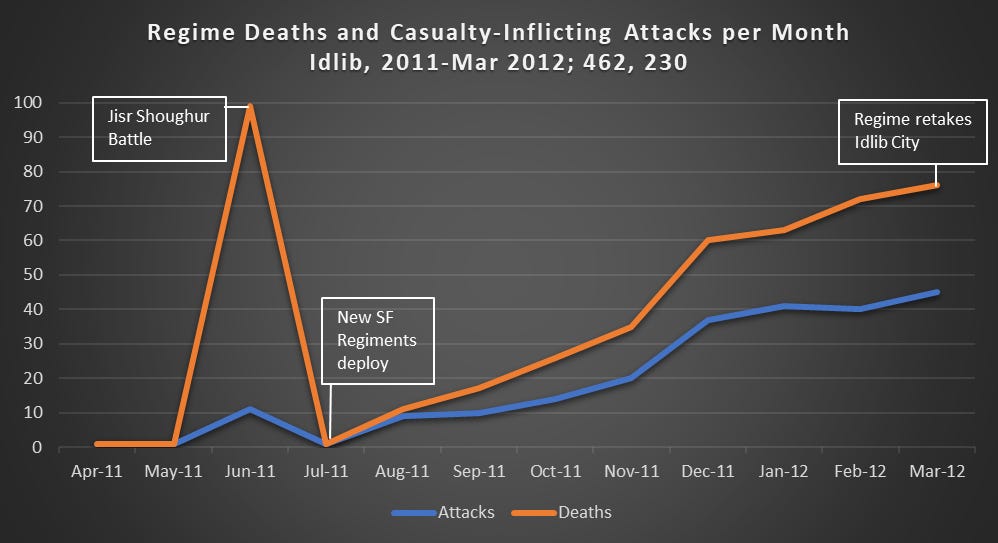

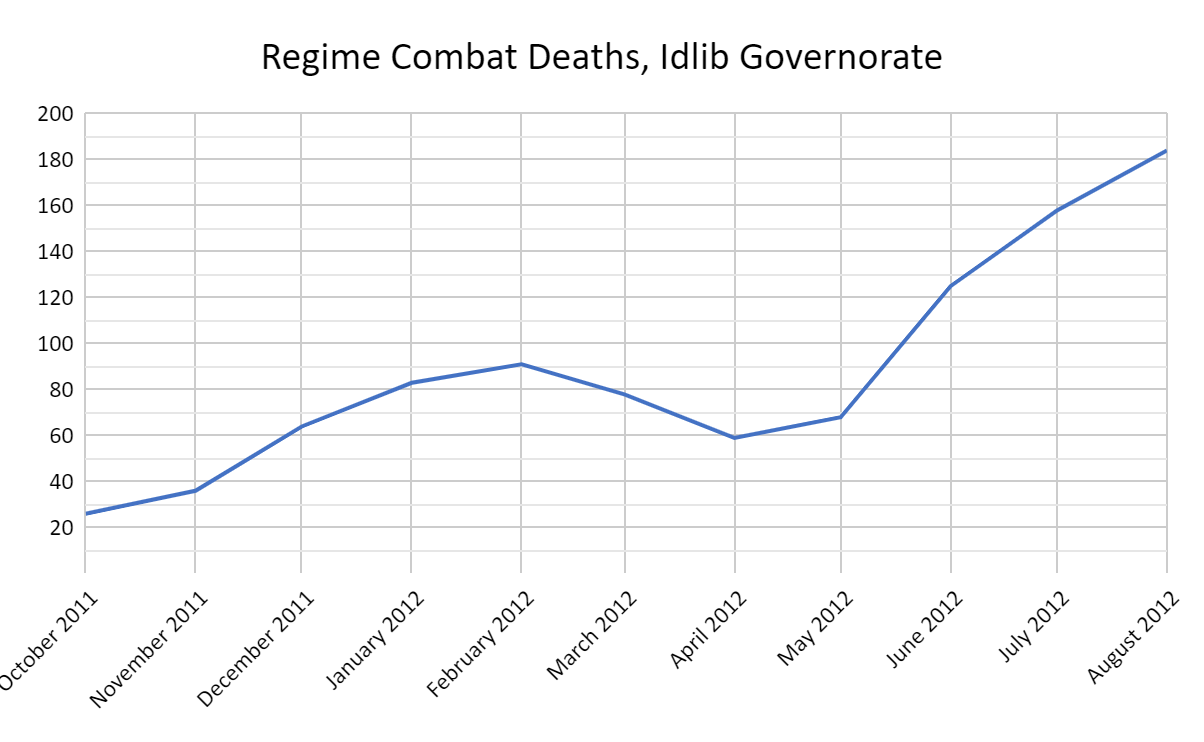

Still, successful attacks against regime forces in Idlib over the next months were rare, and mostly focused in Jabal Zawiyah. Only fifteen security forces were reported killed between June 10 and the end of August 2011. However, on August 17 members of the Free Officers Movement released a statement announcing the formation of “deterrence groups” which would actively protect so-called “safe” villages from regime raids. In the announcement, the officers claimed to have conducted their first operations against security forces who were attempting to raid villages in Jabal Zawiyah that morning:

This attack resulted in the death of a regime Lieutenant Colonel, the first senior officer killed in Idlib.

Many of these attacks targeted checkpoints and patrols, killing everyone from police, to mukhabarat, to soldiers. Regime “martyrdom” biographies provide an interesting insight into some of the units clashing with the revolutionaries at this time. For example, on August 23 two military intelligence members were killed on the road south of Kafr Naboudeh after their unit conducted a raid in the town, which sits on the southern edge of Jabal Zawiyah. In just the five months between the start of the revolution and their deaths, this unit had deployed to the Damascus countryside, Idlib, Hama, and Jisr Shoughur. Similarly, a unit belonging to the State Security that was ambushed while conducting a raid in Binnish in October had previously participated in operations in Douma (Damascus) and Baniyas (Tartous).

These specialized mukhabarat units moved across the country deploying to hotspots as support for the local branches. This includes the Military Intelligence’s “Raid Company” (Branch 215), the State Security Anti-Terrorism Branch (295), and the “Special Tasks Battalion” of the Ministry of Interior’s Internal Security Forces - all of which suffered casualties during the 2011 Idlib insurgency.

As these attacks continued, the regime deployed additional reinforcements to the governorate. By Fall 2011, elements of four more army brigades (the 1st Division’s 58th Brigade, the 3rd Division’s 47th Brigade, the 11th Division’s 87th Brigade, and the 18th Tank Division’s 134th Brigade) and two more special forces regiments (the 54th and 47th Special Forces Regiments) had arrived.

Despite the significant deployment of military units, the regime’s general strategy in Idlib during the first year of the war ultimately provided crucial breathing room for defectors and locals to organize into armed groups. Rather than occupy every village across the countryside, security and military forces concentrated themselves in three main military camps in central and southern Idlib, and established secondary headquarters inside the major cities like Idlib and Jisr Shoughur. The vast majority of the governorate, however, was controlled via “checkpoints” on the outskirts of towns and along the major roads. These were not checkpoints in the normal sense, but more akin to small military bases. These positions appear to have always had at least one armored vehicle such as a BMP - and in later months increasingly had tanks - and usually had around at least twenty soldiers and mukhabarat officers.

This approach meant that many villages in the governorate were effectively free already by the second half of 2011. Captain Ammar al-Wawi recalls the atmosphere in Jabal Zawiyah when he arrived in the area following his defection in early August:

“The brothers [the Free Officers Movement] received us in Jabal al-Zawiya, and they honored us, but there was no complete [military] organization. The demonstrations were peaceful, and the revolutionaries carried weapons and protected the roads. All the roads were monitored by the rebels for any movement of an intelligence patrol from Maarat al-Numan, for example.”

According to al-Wawi, the Free Officer’s Movement was able to secure and liberate the core of Jabal Zawiyah by that August. Activists regularly posted videos throughout 2011 and 2012 from many of the smaller villages in central Jabal Zawiyah showing weekly protests against the regime and in support of the revolutionaries. These liberated villages were connected by a string of opposition checkpoints, manned by locals usually armed with simple hunting rifles or nothing at all whose main duty was to check IDs for anyone who was a known or suspected regime spy, mukhabarat agent, or member of the pro-regime shabiha militias trying to infiltrate their towns.

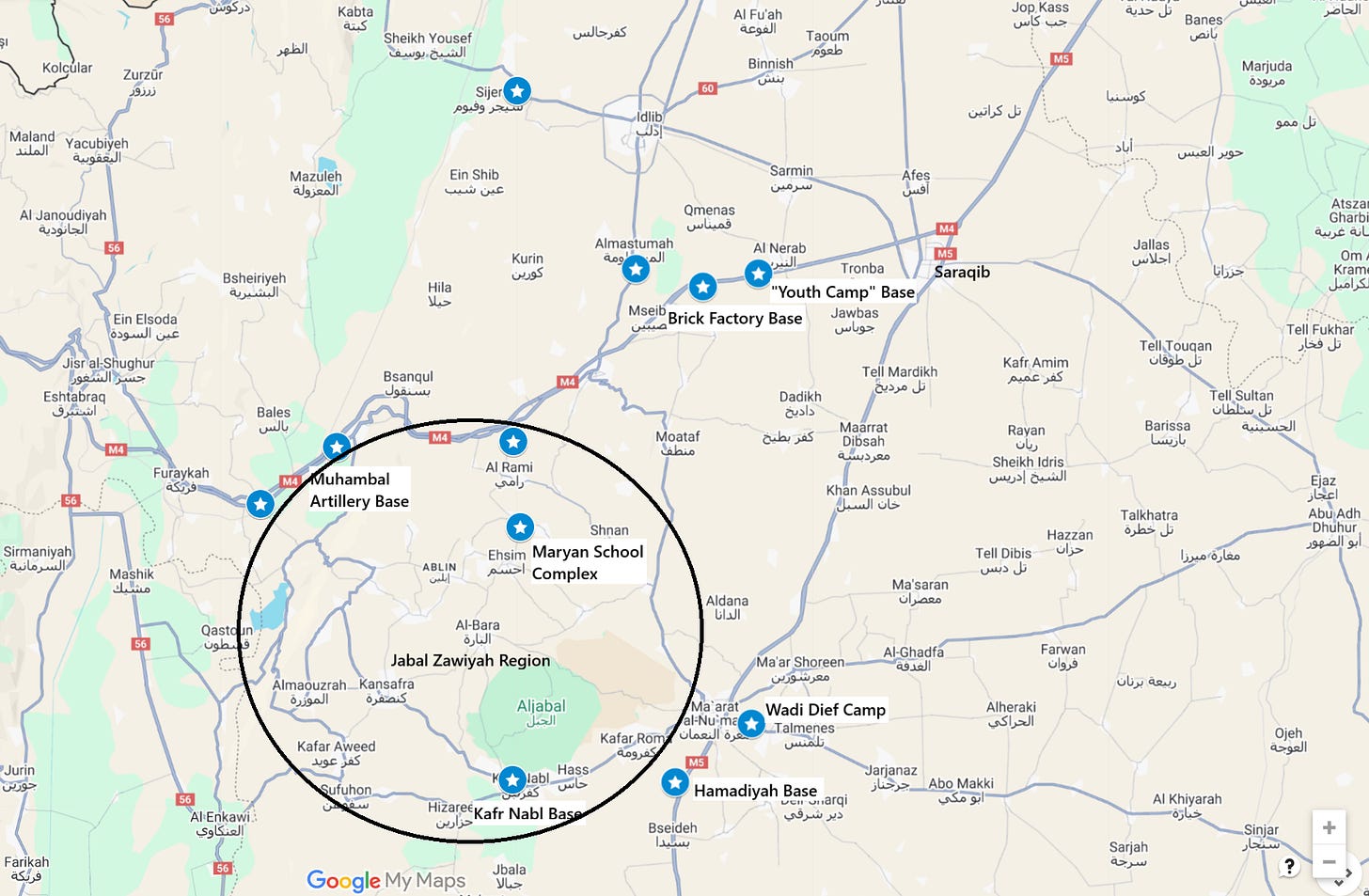

This checkpoint system was also used to alert communities and armed groups when the regime’s military forces began to move. Large bases had been established in Kafr Nabl and in the Marayan school complex, on the south and east sides of Jabal Zawiyah, as well as a string of smaller bases along the M4 Highway between Ariha and Muhambal to the north. While many of Jabal Zawiyah’s villages were never occupied by the regime, security forces would deploy from these positions in columns of armored vehicles and transport trucks to intermittently raid the rural area. The opposition’s checkpoint system gave locals enough time to hide wanted people, dismantle their checkpoints, and prepare ambushes. Meanwhile the Free Officers Movement decided in August to direct all defectors from the surrounding regions to Jabal Zawiyah. This quickly bolstered the small group of original FOM officers and allowed the group to begin conducting its own operations against regime positions resulting in the capture of soldiers, weapons, and equipment.

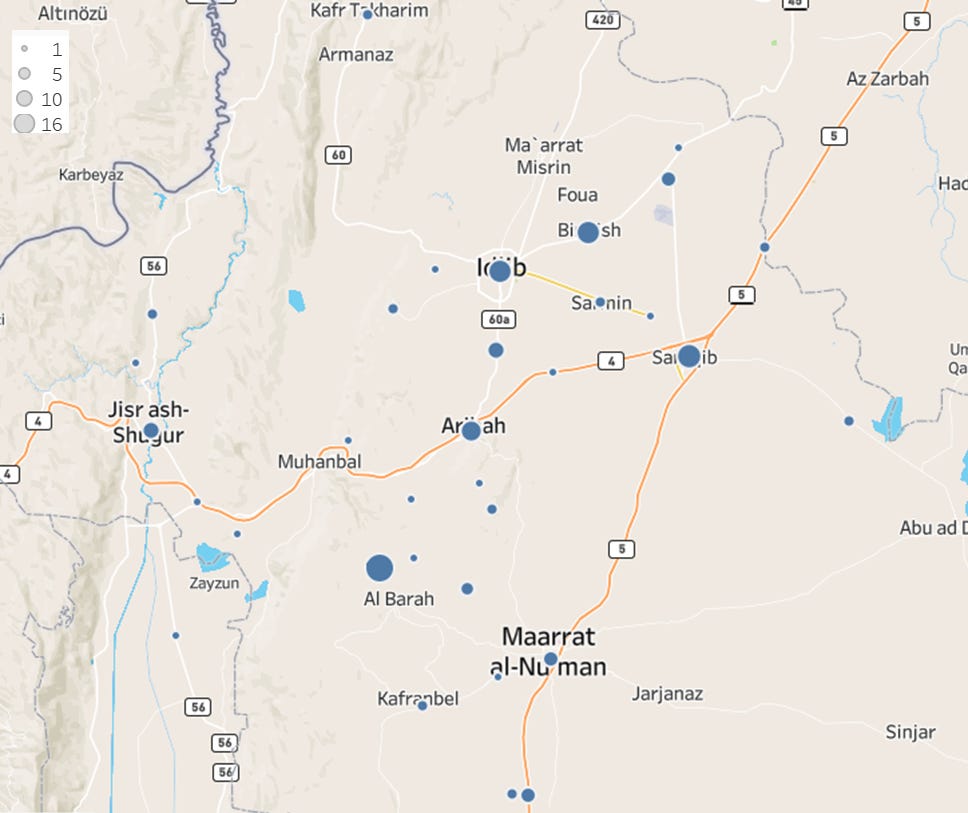

However, as more security forces deployed to the governorate, regime raids increased and checkpoints spread, putting new pressure on these communities and on the growing armed opposition. Armed activity increased in September – still centered in Jabal Zawiyah but now once again emerging in the Jisr Shoughur countryside and expanding for the first time to the countryside east of Idlib city. At least 17 security forces were killed during this month – more than the previous two and a half months combined.

A clear shift in operations began in October, with attacks becoming more frequent, widespread, and deadly. As military expert Joseph Holliday wrote at the time:

“Starting in late October 2011, a capable rebel group conducted a series of effective ambushes and raids along the roads and highways that bordered the mountainous Jebel al-Zawiya region of northern Idlib province.”

What Holliday missed, and is more evident thanks to release of regime funeral notices in later years, is the growing attacks in the first half of October across new parts of Idlib. While Jabal Zawiyah remained the core of armed activity, deadly attacks were now being conducted in the countryside east and west of Idlib city, particularly in the Binnish-Saraqib-Taftanaz triangle.

Meanwhile violence in Jabal Zawiyah continued to increase in October and November 2011, including successful IED attacks on regime officers. Opposition armed groups also began to successfully kill security forces inside Idlib city during this month.

Attack lethality and sophistication also appears to have noticeably improved during the period. Opposition groups were now killing multiple soldiers in each attack at a far higher rate than in previous months. As Joseph Holliday described the fall of 2011:

“By the end of November, rebels operating out of the isolated mountain range [Jabal Zawiyah] averaged an attack each day, descending from their high ground to conduct raids and ambushes near Syria’s primary north-south highway and near the key east-west highway that connects Aleppo to Syria’s coast.”

Armed attacks continued to grow through December, though with a renewed emphasis on Jabal Zawiyah as compared to elsewhere in the governorate. At least sixty soldiers were killed this month, nearly twice as many as in November. On December 17 alone at least 17 soldiers were killed across Jabal Zawiyah. Jospeh Holiday’s report from early 2012 highlights that “In December, a series of videos showed increasingly large and confident groups of armed men demonstrating in towns that seemed entirely beyond the regime’s reach.”

At the same time, anti-regime insurgents significantly escalated their attacks in Idlib city. Between December 2011 and the end of January 2012, nearly all of the city was liberated, the remaining regime forces isolated to the major government office blocks and checkpoints outside the city.

This increased attack tempo paralleled a surge in armed group formations across Idlib in November and December, joined by ever increasing anti-regime demonstrations. At least nine new armed factions published videos announcing their formations between mid-November and mid-December, according to data collected by the Syria Memory Institute and shared with the author. These groups were often founded and led by defectors but heavily staffed by locals, increasingly arming themselves with battlefield captures. Meanwhile, on December 30 an estimated 250,000 people took to the streets across the governorate in mass protests against Assad.

It was clear by the end of the year that armed groups had made drastic improvements to their supply lines and coordination. Attack sophistication and lethality continued to increase, with ever-growing competency and manpower opening new possibilities for insurgent-style activity, especially targeted assassinations. The local nature of the armed groups, as well as the fact that many of the FSA and FOM leaders had roots in Jabal Zawiyah, resulted in decent levels of coordination between the factions during this time.

The Regime’s Offensive

The intensification of fighting across Idlib, combined with the regime’s appointment of the head of its Special Forces Command, Maj Gen Fouad Hammouda, as the overall commander of Idlib operations at the end of November, resulted in a further expansion of military forces deployed to Idlib in early 2012. Many of these units arrived from Homs, where the regime had conducted a major offensive against rebel forces inside the city in February and March 2012. These units first participated in a March 2012 operation to retake Idlib city before establishing themselves alongside the pre-existing units based in Mastoumeh, Wadi Deif, and Jisr Shoughur. Many of the core areas of operations remained the same as in 2011, but there now appeared to be a particular emphasis on reinforcing the border areas from Jisr Shoughur to Bab al-Hawa, as this had become a critical weapons and human smuggling node for the broader northwest Syria insurgency.

Three more special forces regiments arrived in Idlib by early 2012, bringing the total operating in the governorate to six. The new units belonged to the 15th Division’s 35th Regiment, the 14th Division’s 36th Regiment, and the independent 48th Special Forces Regiment, all of whom established positions along the Turkish border.

These special forces regiments were supported by three new army brigades, including the 3rd Division’s 21st Brigade and the 7th Division’s 88th Brigade which deployed to Jabal Zawiyah. The 1st Divisions’ 76th “Death” Brigade, meanwhile, was tasked with raiding dozens of towns across the governorate in February 2012, leaving a bloody trail of victims and disappeared people in its wake.

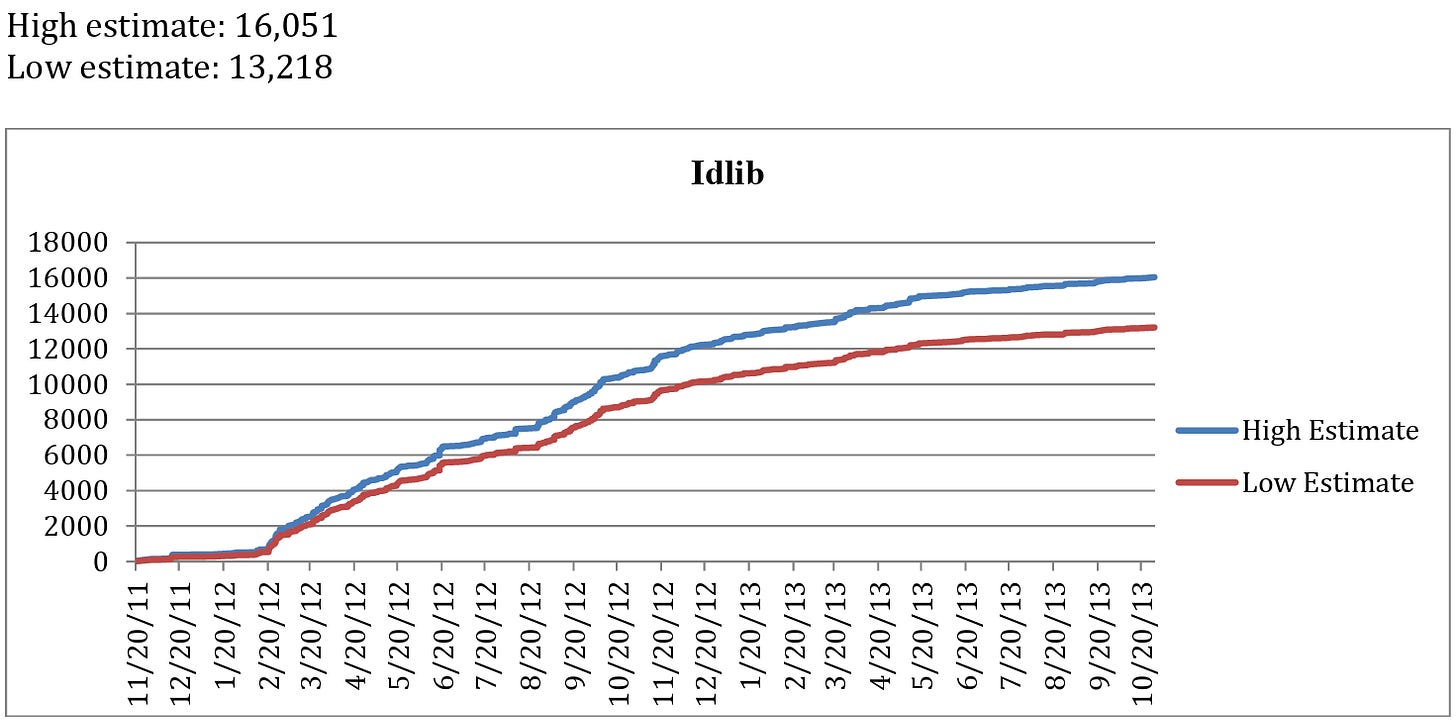

By the time the regime had recaptured Idlib city in March 2012 it had lost around 500 soldiers, police, and intelligence members in the governorate. The next half-year would see a marked escalation in fighting, the regime suffering more than three times as many dead and huge numbers of captured soldiers. The fighting would fall particularly hard on the special forces units.

The Opposition Spreads

The regime’s security approach in Idlib during this time still relied heavily on checkpoints and bases along major highways, but with an increased reliance on using large armored columns to raid towns and respond to attacks. The regime had effectively ceded much of the urban space across the governorate, forced to actively deploy to and clear towns if it wanted to establish more concrete control. This resulted in the increasingly frequent event of armor columns storming towns, with rebel fighters either withdrawing entirely or engaging in short clashes against their more powerful opponents. These operations were rife with war crimes. Human Rights Watch documented dozens of cases of summary executions, mass arrests, and the torching of homes in just five towns the army entered in late March.

Areas of control during these first half of 2012 are therefore difficult to assess. This period marked the slow shift from insurgency to more conventional war, and with that the presence of armed forces from both sides fluctuated greatly. Nonetheless, the main north-south and east-west highways running through the heart of the governorate remained largely under regime control.

As larger cities lying on less strategic roads, such as Saraqib and Sarmin, were largely liberated, regime forces reverted to a surround-and-shell approach. Incursions became rarer, and usually only lasted for one or two days. This was part of a new nationwide strategy adopted by the regime following its initial victory in Homs city in February and March 2012. Joseph Holliday described this approach as:

“The regime began to employ artillery decoupled from ground force operations by periodically shelling towns and neighborhoods without ever mounting operations to clear them. This evolution was largely a result of Assad’s lack of available ground forces, particularly in northern Syria where troops became pinned down in strongpoints across the countryside. By shelling opposition areas from a distance, the military was able to limit casualties and defections among its already overstretched forces.”

An International Crisis Group report from later in 2012 described the strategic evolution as one moving “From strict counterinsurgency … into collective punishment and verged on wholesale scorched earth policy.”

In late February the army stepped up offensive operations across the governorate, seeking to stamp out the growing armed opposition. First, on February 19 security forces cut off the highway leading into Jisr Shoughur, preventing civilians from entering or leaving, and set up cordons around two nearby villages. Two days later, the regime initiated a two-and-a-half week long campaign across the Idlib countryside that would culminate with the March 10 offensive to re-capture Idlib city. Regime forces stormed more than a dozen towns and villages across all parts of Idlib, ostensibly in search of armed opposition fighters, anti-regime activists, and journalists. Houses were burnt down, locals were executed, and many were arrested. Meanwhile tank and artillery units enacted partial sieges around other towns, such as Binnish and Saraqib.

The regime’s operations and widespread abuses fueled the growth of new armed opposition groups in Idlib in February and March. A Carter Center chart estimating the number of opposition fighters in Idlib during this period – based on video announcements of armed groups – shows the first significant jump occurring in the second half of February 2012.

Likewise, data collected by the Syria Memory Project and shared with the author shows at least 14 armed group formation announcements in Idlib between February 9 and February 28. Most of these announcements were for groups operating in Jabal Zawiyah, but also some in Khan Sheikhoun, Sarmin, and north of Idlib city. This trend continued throughout the spring, with at least 21 new groups announced in March, and 28 more in April.

However, the rapid expansion of the armed opposition did not immediately translate into effective resistance against the regime. The factions still lacked heavy weaponry to deal with the regime’s biggest advantage: its armored vehicles, and in particular tanks. Opposition groups largely relied on IEDs to damage to this equipment, suffering from a lack on RPGs and especially ATGMs, which would become ubiquitous in northwest Syria in later years.

The difficulty the regime faced was the sheer geographic space that it needed to occupy. Unlike Homs and Damascus, whose cities and countrysides were pockmarked by loyalist communities and large military bases, the regime was facing a near-governorate wide rebellion in Idlib and had very little pre-war infrastructure to utilize. Every large town needed multiple checkpoints, each one staffed with multiple armored vehicles, every supply and patrol convoy needed to be large enough to dissuade ambushes, and key roads needed to be held by strings of well defended positions. This inherently forced security forces to confine themselves to checkpoints and bases spread across the governorate, limiting the usefulness of their armor advantage.

Security forces were further hamstrung by widespread paranoia over defectors and deserters. Idlib’s proximity to the Turkish border and overwhelmingly anti-regime population made defection much more enticing – though still incredibly dangerous – compared to other parts of Syria. In response, regime commanders had already begun sidelining significant contingents of the deployed regiments and brigades, confining those thought untrustworthy to the large bases in central Idlib like Mastoumeh and Wadi Deif – or simply detaining them – and therefore limiting the manpower available to spread to rural checkpoints and send on raids.

Thus, despite this growth, the regime’s raids had a clear dampening effect on the opposition’s operations in late spring. April saw a drop in regime deaths for the first time since July 2011. Attacks in Jabal Zawiya were less deadly during this period, with most activity occurring in and around Idlib city, where the opposition had launched an insurgency following the city’s capture.

Taking Ground Against Assad

A clear shift in the armed opposition’s operations began in May. The opposition began conducting both more serious ambushes and more frequent attacks around the region’s outskirts, forcing the regime out of parts of Jabal Zawiyah. Sixteen soldiers were killed on May 29 alone during the liberation of the village of Maghara in Jabal Zawiyah and frequent, deadly attacks renewed in and around Maarat al-Numan for the first time in several months. The most significant development, however, was the sudden widespread deadly attacks across northern Idlib. These developments likely reflected the significant growth in armed groups both locally in the Maarat al-Numan countryside and more broadly across the Turkish border areas in Idlib and Aleppo throughout March and April.

The regime’s operations in the early spring of 2012 were successful in re-asserting security presence across parts of Idlib and reinforcing and expanding many of the army’s points in the governorate. However, this victory was short lived thanks to the rapidly evolving developments within armed opposition networks internationally and within the broader northern Syria region. Foreign financing for more Islamist-aligned factions had steadily grown since late 2011, and significant weapon shipments began to flow into the north starting in March 2012. These factors, combined with a broader restructuring of opposition military councils and steadily improving coordination between factions, led to the rapid collapse of the Aleppo countryside in May.

The regime’s grip over Idlib began to irreparably slip in June. Confirmed regime losses more than doubled, with at least 124 soldiers killed across Idlib in June compared to just 58 in May. Some regime units in Idlib were tasked with supporting the flailing forces in rural Aleppo, forcing large convoys out of their secure bases and opening them to ambushes.

On June 27, for example, a battalion of the 556th Special Forces Regiment attempted to redeploy from Mastoumeh to the Aleppo countryside but was ambushed as it approached the central Khan Sabeel checkpoint. At least two tanks, two BMPs, and one transport truck were destroyed and at least one BMP captured by the local affiliate of the increasingly power Suqour al-Sham faction. At least 15 soldiers, including Colonel Nashat Al-Amer who the opposition had previously claimed was the commander of operations in Jabal Zawiyah.

A journalist embedded with Suqour al-Sham in mid-June claimed that 25% of Jabal Zawiyah was liberated. But the largest towns in central and southeast Zawiyah still remained under regime control and staffed with multiple special forces battalions. Over the next month, local armed factions and Suqour al-Sham affiliates liberated a string of villages and regime checkpoints along the central southwest-northeast spine of Jabal Zawiyah. By early August, regime positions had been isolated to the southern Kafr Nabl-Maarat al-Numan highway and the northern area around Ariha.

Bayoush Returns From the Dark

Meanwhile, Fares Bayoush had been trapped in detention facility in Damascus since July 24, 2011. He was first kept in a bare solitary confinement cell, sleeping on the concrete with only a blanket for warmth. Later he was transferred to a group cell with 80 other men, too packed to sleep on their backs and stripped down to their shorts. The cell had no ceiling, exposing them to the winter rains and summer sun.

On June 10, 2012, Fares was released from his 11-month horror:

“The jailer came and told me to get ready for my release. They brought me a military uniform and military boots. He told me that we were going to meet the "Commander General," as they called him. Of course, he handcuffed me and put a blindfold on me. We went to an office and sat there waiting. Colonel Sultan Tinawi, who was the director of Major General Jamil Hassan's office [head of the Air Force Intelligence], arrived. He reprimanded the jailer for handcuffing me and told him that I was an army lieutenant colonel (of course, the jailer didn't know my job title, as my name was a number in the prison). He then told me that we would enter the Commander General's office shortly. We went together to the office, which was very large and had many external surveillance screens I had never seen before. Hassan stood from behind his desk, came to the entrance, and shook my hand firmly. He said, "You have been imprisoned unjustly for a year and have not been proven guilty, but you know the circumstances of the country." We then sat down, and he offered me a cigarette and a cup of coffee, and we began to talk. Then he asked me if I had any special requests. I asked him to release some detainees whom I found to be unjustly treated, and he did so immediately while I was with him.”

Fares then asked about his family, who he was told were in Kafr Nabl, and was informed he would soon be flown back to Deir Ez Zor to report to work. Fares knew nothing about what had transpired sine July 2011, since, as he says, nearly all the men detained alongside him were innocent and thus had not been active in the armed uprising. When Fares asked Major General Hassan about Kafr Nabl, he was told to not visit the town. “I asked him why, and he replied, "You will know when you get out."

Fares then went to the Officers Club to meet an old Air Force friend, Colonel Hassan Hamadeh. As they spoke about the developments since July 2011, Hamadeh told Bayoush he intended to take his jet and defect to Jordan. “I encouraged him to do so, and when he defected 11 days later, I was almost arrested again because of him, because they all knew how strong our friendship was, and I must have been aware of his plan. General Jamil Hassan called me, and we had a long conversation. I then realized I couldn't stay in the army any longer, and so I coordinated the defection of Lieutenant Colonel Abdul Karim al-Yahya, Captain Salim al-Birini, and myself.

“It was a very difficult three weeks. My concern was securing my family first after they came to Deir ez-Zor to see me. So I sent them to Kafr Nabl first, in a very complicated way, so as not to draw attention to the fact that I had defected. Then we agreed on the day of the defection, July 1. I got into my car in the morning as usual, and the lieutenant colonel and the captain rode with me. We headed east toward the airport. But as soon as we arrived at the airport entrance, I continued as quickly as possible toward the city of Al-Muhassan, and from there I announced my defection. With me was another lieutenant colonel from Suwayda, named Hafez Al-Faraj.

“We chose Al-Muhassan because it was liberated, and we coordinated with some rebels there to receive us. The head of the military council was Lieutenant Colonel Muhannad Talaa, and there were many defected officers from most of the provinces. I stayed in Al-Muhassan for several days, then entered the city of Deir ez-Zor, which was under siege. There, I formed the first operations room under my command, and stayed there for about a month. Then I returned to Al-Muhassan for two days.”

From there, I went to Kafranbel by road through the desert with the help of a guide who knew the way. We fell into an army ambush, and one soldier was killed and another was wounded. I, Lieutenant Colonel Hafez al-Faraj, and Captain Salim miraculously escaped, while Lieutenant Colonel Abdul Karim remained in Mohsen until ISIS took control. He then came to Kafranbel and assumed the position of Chief of Staff of the Northern Division, which I commanded.

At this point Fares had been freed for over a month but still hadn’t returned to his home. He called some friends who were part of the city’s armed movements and asked them to pick him up in Jarjanaz, in rural eastern Idlib, where he would arrive from Deir Ez Zor, so that they could safely take him around the regime positions and into Jabal Zawiyah.

Fares, Lieutenant Colonel Hafez, and Captain Salim drove through the central Syrian desert on August 5 alongside a small groups of fighters. Along the way they were ambushed by regime forces, who killed one of the fighters, but the three officers managed to escape unharmed. In Jarjanaz, three Kafranbel fighters met them, Ahmed Al-Nahar, Mahmoud Al-Bayoush, and Mahmoud Al-Ghazoul.

“We left Jarjanaz, avoiding all main roads. As we approached Kafranbel, we saw black smoke columns, so I asked them, "What are these?" They said there appeared to be military activity against the checkpoint in Kafranbel.” It was August 6, and the battle for Kafr Nabl has just begun.

“Upon arriving at the entrance to Kafranbel, a group of young men stopped us and warned us not to take the road due to clashes. So we took a path through the orchards until we reached my house. I left my guest, Lieutenant Colonel Hafez, at home and immediately went to the area of the clashes and joined them.”

Liberating the Heartland

Four days later Kafr Nabl was liberated and regime forces pushed back to Marrat al-Numan. All of Jabal Zawiyah was now free, the regime reduced to holding the Idlib-Latakia highway on the northern edge and the Idlib-Hama highway to the east. While the fighting raged in Kafr Nabl, other FSA factions were conducting operations on the northern side of Jabal Zawiyah. On August 9, 17 soldiers from the 7th Division’s 88th Brigade were killed in the village of Bzabor, just south of Ariha. In late August, the months-long skirmishing around Ariha came to a head as opposition factions announced a new offensive. “The Battle of Unification” saw reinforcements from across the governorate arrive in and around Ariha, hoping to permanently liberate the city and secure the Jabal Arbaen region to the north of Jabal Zawiyah.

In Kafr Nabl, Fares quickly took command of his town’s fighters and formed the Liwa Fursan al-Haq faction, and later took command of the Northern Division, one of the most prominent FSA groups in Idlib. Colonel Yahya Abdul Karim would stay in Deir Ez Zor leading opposition forces until ISIS captured the region, at which point he joined Fares in Idlib and became the Chief of Staff of the Northern Division.

Fares describes this period as one in which the army was suffering from bad morale and increasing losses while the opposition factions were increasingly coordinated, experienced, and well armed. “Each time the FSA liberated an area they gained experience and gained weapons and coordination improved, as all of this increased it led to FSA being able to do bigger attacks, more than just checkpoints,” he recalls. Regime forces were no longer on the offensive like earlier in the year, now they relied on increasingly fortified bases along major highways, abandoning many of the smaller villages and unable to defend the larger towns. That fall would see the collapse of regime forces across nearly the entire Idlib-Turkish border, opening the flood gates for human and materiel support to opposition factions across the ideological spectrum.